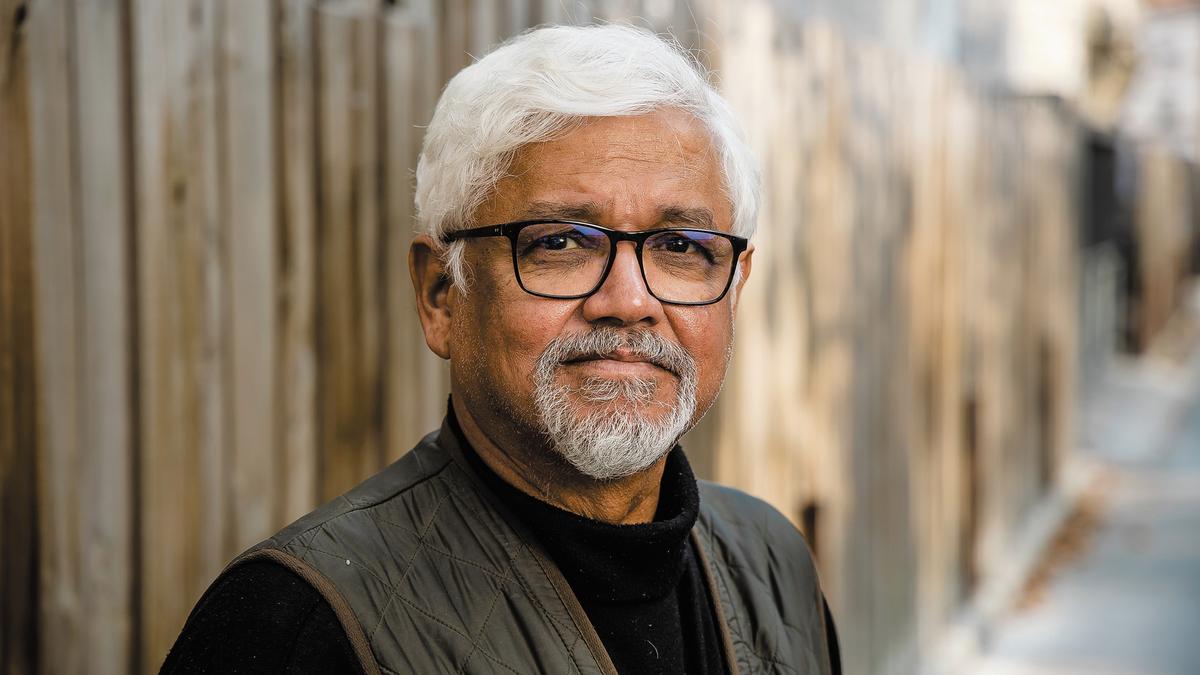

Amitav Ghosh thinks of the West as an empire of chaos. “Look at the mess the West had made,” says the award-winning writer, who was recently in Bengaluru to release his latest book, Wild Fictions, a collection of 26 essays centred around many of the themes he has explored in both his fiction and non-fiction over nearly four decades. Some of these include the long shadow of colonisation, the planetary crisis, displacement and migration, a mapping of south-south connections, neo-imperialism, the limitations of science, and so much more.

“The pieces in this collection are about a wide variety of subjects, yet there is one thread that runs through most of them: of bearing witness to a rupture of time, of chronicling the passing of an era that began 300 years ago, in the eighteenth century,” he writes in the book’s introduction, adding that this was the period that saw the birth of modernity and industrial civilisation, in which, under the leadership of the British empire, the West tightened its grip over most of the world, culminating ultimately in the emergence of the U.S. as the planet’s sole superpower.

“Starting with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the ‘unipolar moment’ peaked at the turn of the millennium and then ran into a series of profound shocks that began in 2001,” writes Ghosh, who was awarded the Erasmus Prize 2024 “for his passionate contribution to the theme ‘imagining the unthinkable’, in which an unprecedented global crisis — climate change — takes shape through the written word.”

In the introduction to the book, you quote a term coined by the writer and philosopher Antonio Gramsci, who refers to the time between the death of the old world and the struggle of the new world to be born as “the time of monsters”, something that you thought the world again entered after 9/11. Unlike Gramsci’s monsters, who are political creatures, our monsters today are an amalgamation of both the natural and the political. Could you expand a little on that today, especially given recent significant climate events, such as the California wildfires, the toxic air bubble that plagues the Indo-Gangetic plains in winter or the multiple floods occurring in South and Southeast Asia in the last year?

These things are really monsters in the sense that they are overdetermined by various causes. You can’t reduce them simply to climate, bad management or bad planning. All of those things are coming together. It’s like all the frailties in our patterns of development have suddenly come together for a perfect storm to be exposed in a way that has never been seen before.

The California fires are a very good example. On the one hand, there is a major climate impact that dried out the soil and has been doing that for a long time. This is the longest period without rain in winter that has ever happened in Southern Californian history. That played a very important part in desiccating the soil and laying the groundwork for these devastating fires.

However, settlement patterns also played a very important role in all of this; real estate interests have built ever denser housing along Malibu, for instance. And because it’s sea-facing, there’s a huge property premium, which creates this concentration of wealth. So wealthy people who seem to have no common sense have moved there in larger and larger numbers even though they know Malibu has been devastated by fires for over a century. There’s nothing secret about these fires. They’ve happened repeatedly.

Climate deniers start saying that this is nothing new; it’s always happened. But the intensity of it is new, determined by multiple factors. Politics plays a very large part in it because real estate interests are some of the major financiers of politicians. In California, there have been repeated initiatives to try to prevent building in locales like Malibu, (but) they’ve always been defeated by the real estate interests.

One of the problems that arises now is that they use various kinds of fossil fuel derivatives as building materials..laminates…various kinds of siding. They’re all spin-offs of fossil fuels, and they become extremely flammable under certain conditions. That is, in effect, what’s happened in this region. There were politicians who introduced bills trying to force the real estate industry to use safer materials. But they [real estate interests] fought that tooth and nail and ultimately managed to defeat the bill.

The real estate industry is one of the most dangerous industries in the whole world; the capitalist system under which building occurs has every incentive to move into areas that are not right for settlement. For real estate interests, this is easy money…a win-win situation because they’re not committed to the long-term risk. They build, sell, and move out, and that’s the end of their commitment. And the risk is borne by those stupid people who buy these things.

You argued earlier that literary fiction does little justice to climate change and what it means for the Earth’s future. Do you think this narrative has changed, and has there been some attempt to mainstream eco-fiction in the last few years?

It has certainly become part of the mainstream discourse, especially from 2018 onwards. But it is not just climate change. We are in a planetary crisis, which includes biodiversity loss, species extinctions, new pathogens and AI.

It is not like writers were not writing about these issues. They’ve always been writing about it. The problem is not with the writers. I think the problem ultimately lies in the wider ecosystem of culture. Even if writers wrote these books, mainstream reviews would not pick them up because they would say that these are just like a genre, you know? They’re not serious. That’s a very major problem, and that hasn’t changed.

One of the reasons why I’m increasingly hesitant to speak of just climate, you know, is because this has been picked up and turned into a market opportunity even though we can all see that the climate crisis itself is the greatest market failure that has ever happened. Unfortunately, the world led by the United States has decided to embrace market-based solutions, where we know that market-based solutions won’t work

Climate change-driven human migration has historically been a key aspect of the human condition, whether it be the great migration out of Africa or how the Little Ice Age caused people to flock into towns and cities. Are there any parallels or lessons to be learnt from this past, especially given that the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) predicted that there would be about 1.2 billion “climate refugees” in the next two decades or so?

One very important lesson that we should absorb from this is that terms like “climate migrants” and “climate migration” are very reductive terms, and I would caution against thinking of climate migration as a singular thing.

Nobody migrates for just one reason. There are always multiple reasons: Sunil Amrith, the historian who’s written extensively about migration in the Bay of Bengal, for example, points this out. In fact, there are now innumerable articles, books, and essays that hotly dispute the term climate migration.

Climate is one of many factors that play a part in people’s large-scale movements. The first essay in my book, for example, is about migration, for which I did a lot of research on young migrants who had crossed the Mediterranean and walked over the Balkans. And it was very interesting to talk to them.

You know, this whole phenomenon of migration, when it’s covered in the Western press, is almost always covered by journalists who don’t speak the languages of the migrants. So they get, I think, a very false picture of what is actually operating there. Migrants are extremely intelligent, and they know what sort of story Western journalists want to hear.

Because I speak the languages of the migrants, I would hear completely different stories.

You also write that many of them regret having made this decision to move… that their dreams and expectations of the West, shaped by cultural colonisation, did not measure up to reality.

For the last many centuries, but especially intensifying since the Washington consensus (a term used to denote neoliberal economic policy prescriptions made for developing countries in the 1980s and 1990s, including deregulation and reduced public spending, made by Washington DC-based institutions like the World Bank and IMF) the West has very powerfully invested in propaganda about itself as the best, the most affluent, and the most free. Ultimately, this influences gullible people, and it’s a really sad thing.

I mean, all these young migrants I spoke to…90% of them regretted having set out on this journey. Because look at the lives they lead over there…10 to a room, discovering that there is no work for them. I mean, Italy can’t provide work for its own people, how is it going to provide work for these migrants?

It is entirely based on a kind of fantasy, and we should never forget that a very major aspect of this fantasy depends on social media. These technologies have been so profoundly transformative that we don’t even now recognise or acknowledge how disruptive they have really been. Think of that Gujarati couple who took their children and froze to death on the Canadian border. What kind of madness is that? They’re from families that are perfectly fine in Gujarat. I looked at a lot of the cases. They were from educated middle to upper-middle-class families…school teachers, etc. What did they think they would get in America that they don’t have in Gujarat?

But you can’t stop people from aspiring for things…

You can’t. And that’s why this is an unstoppable phenomenon. You’ve created a society that’s built on creating appetite and creating discontent with your present circumstance. And that’s got a long, long history of colonialism.

When colonisers first went to Nigeria, for example, they saw that people were, you know, they would cultivate enough for themselves, but they didn’t want to grow anymore because they were not interested in accumulation. They wanted to spend time with their families and so on.

This was very threatening to them, so sometimes they would actually give people double the land. But it didn’t help because people would only cultivate half the land.

There are these amazing statements by white Americans, you know, who were dealing with Native Americans in the 19th century, saying we have to make them want more because they don’t want enough. And now, this is the tail end of that history. We have very deliberately created this society of demonic desire (where) everyone just wants more, more, more.

Your essay, The Town by the Sea, is a very moving account of a visit to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands immediately after the 2004 tsunami, which elucidates the ecological vulnerability of the space. What are your thoughts about the recent “Great Nicobar Project” and plans to develop it in a Hong Kong-like manner?

It’s horrifying. I mean, it’s the perfect example of disaster capitalism, you know, because they seized upon this after the 2004 tsunami, and in the aftermath of that tsunami, they just cleared the native peoples off the land. At that time, there was some promise of bringing them back, but they haven’t been allowed to return. They desperately want to return but haven’t been allowed and now have come to recognise that they’re going to be stuck in those camps forever, like Palestine.

We are now practising what you might call auto-colonialism, implementing those colonial policies on a vast scale for the benefit of a tiny group of wealthy capitalists. It is so horrifying that it’s difficult to even speak of it, honestly…the craziness that sustains these people.